“If investors continue to see relatively low yields in Europe, then money will flow to higher-yielding markets.

“More widely, investors also need to watch whether China returns to being a deflationary force globally, which could act against the case for central bank tightening.”

Default risk

Many commentators said they were keeping a keen eye on the eurozone, where Italy’s banking system poses no small potential problem, while Greece is by no means sorted when it comes to debt levels.

Figures from Standard & Poor’s in 2016 show that, from 1915 to 2015, there were 189 country defaults and serious debt restructuring. Many of these countries – such as Argentina - are outside of Europe, which is reassuring, given this is a repeat offender. Moreover, some countries don’t exist any more, such as Yugoslavia.

But while these defaults would not have had so protracted an effect on other countries even 60 years ago, today’s increasingly globalised and intertwined economies means this becomes more of a global problem.

Add to this the fact one small country default in the eurozone now will have a significant impact on the rest of Europe as well as the UK and the US, and the situation becomes even more precarious.

Moreover, higher levels of indebtedness at a corporate level, as borrowing has been so cheap over the past decade, could indicate a higher risk of corporate defaults.

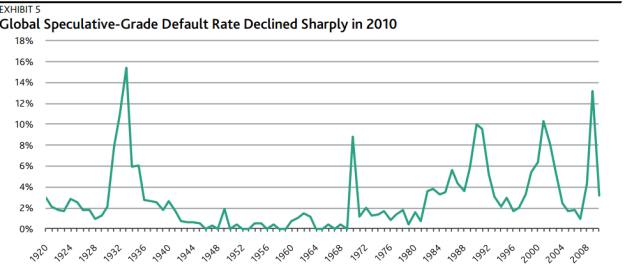

This was seen in great clarity during the recent financial crisis. According to research from ratings agency Moody’s, global corporate defaults had been low, spiking during the Great Depression, the early 1970s at the height of the oil crisis, Black Monday, the Tech Bust, and then spiking again in 2008-2009.

After 2010, defaults have subsided. According to Moody's 61-page research paper, Corporate Default and Recovery Rates 1920-2010, only 57 Moody’s-rated corporate issuers defaulted on a total of $39.1bn of debt in 2010.

By comparison, 265 companies defaulted on a total of $330bn of debt in 2009, with 103 defaults registered in 2008, affecting $280.9bn of debt.

Figures remained low for several years, but then in 2016, fellow ratings agency Standard & Poor’s reported a sharp rise again in corporate defaults.

According to S&P, there were 150 firms defaulting globally. This was a 40 per cent rise on 2015, making 2016 the worst year for corporate stress since the height of the global financial crisis.

Will there be any more exogenous or intrinsic shocks to the market, pushing more companies and even countries to the brink of default – and over? That’s a question for a medium, not a fund manager.

According to Dan Ivascyn and Alfred Murata, managers of the Pimco Income Fund, the fixed income manager’s job is to: “target an attractive distribution and a positive real return” for clients.