The rewards on offer from Asian equity funds have been rich over the past three years. Judged over this timeframe, the Investment Association (IA) Asia-Pacific ex Japan equity sector has beaten its Japan, Global, Europe ex UK, Global Emerging Markets and UK All Companies peer groups. Remove the US equity-heavy Global sector from the equation, and the same is true over five years.

This may come as a surprise to those who have shied away from emerging markets for much of this period. True, the asset class enjoyed something of a renaissance between 2016 and 2017, but it has also suffered from significant bouts of underperformance over the period in question.

The key is that Asia ex Japan, as an investment region, is not quite so closely correlated with the broader emerging market universe as investors may think.

Avoiding countries such as Russia, Brazil and South Africa has helped the MSCI Asia ex Japan index beat the MSCI Emerging Markets – on both the up and down side – in six of the past seven years.

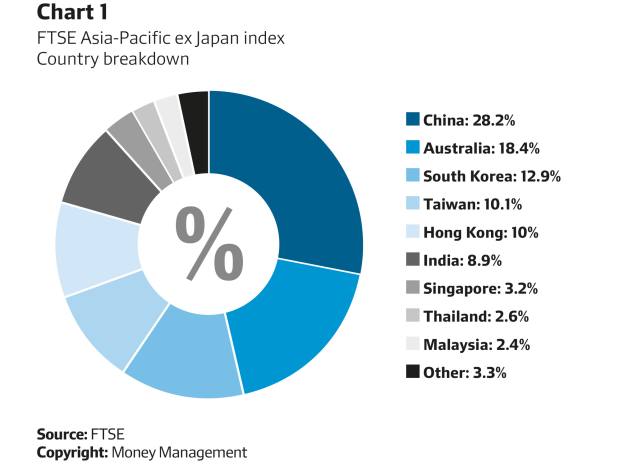

Chart 1 shows the breakdown of a typical benchmark for the region. As the chart indicates, China, Hong Kong and Taiwan account for more than 40 per cent of the index.

Beijing bounce

China, in particular, has remained a source of market volatility since the financial crisis, and being close to that source has meant some violent price swings for investors.

However, investment restrictions mean that funds continue to access Chinese investment opportunities via Hong Kong and Taiwan, rather than the Shanghai-listed stocks which tend to make the headlines when markets become more volatile.

Either way, this volatility obscures the fact that China has helped rather than hindered investor returns since 2009. The old question of whether the country is facing a ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ landing after years of soaring credit growth has yet to be answered. China has yet to ‘land’ at all: instead, it has given a helping hand to risk assets at home and abroad by continuing to boost credit growth.

Lately, this dynamic has shifted again. Beijing has reined in this growth, in part by forcing banks to recognise assets that long sat off-balance sheet.

The Shanghai Composite index has fallen into a bear market for the first time in two years, not helped by the sight of a burgeoning trade war between China and the US. As it stands, the withdrawal of this easy money is just as significant as the fears over the implementation of tariffs as a result of this trade war.

Coming at a time when central banks around the world, most notably in the US, are starting to ease their foot off the accelerator, tighter liquidity could make it difficult for equity markets to make meaningful gains.

Reasons to be cheerful?

But it is not all doom and gloom for the region. There are already signs that tightening is being scaled back in response to the trade dispute. And currency differences, as well as a more mature set of companies, mean the Hang Seng has fallen just 3.8 per cent in sterling terms over the past six months compared with a 17.2 per cent fall for the Shanghai Composite.